The Atrocious Music Collection: #2 in a series

Artist: David Geddes (b. 1950)

Album Title: Run Joey Run

Category: One Hit Wonders

Year: 1975

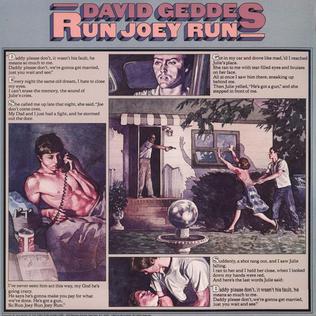

Cover art style: Storyboard

Audio samples: Acquisition: Might have been through Columbia Record Club.

Click on pictures for full-sized images

Teenage-love-death songs are a small genre, arguably peaking in 1964 with Leader of the Pack and Dead Man’s Curve. We can quibble over the exact year, but let’s agree that whenever the teenage-love-death song had its peak, it was long before 1975 when Run Joey Run made an improbable run on the American charts. The whole project is the work of producer Paul Vance (b. 1929) who hired “retired’ singer and law student David Geddes to sing the title song. When it became a hit, the album came into existence and Geddes dropped law school for the mic. We’ll talk about the other songs on the album, but just like the typical buyer of this record, we’re really just here for the first track on side one.

Run Joey Run is a story-song. The song clocks in at under three minutes, and that’s with a chorus (with the complex lyric “Run Joey Run Joey Run Joey Run Joey Run”), and an angelic-choir opening that is reprised several times by Julie. Julie, The Girl, is uncredited on the record, but her faux-little-girl voice skews a bit young for the story, frankly. (This seems to be a theme the record, so prepare to be weirded out later on.) Anyway, in the liner notes, Vance refers to David Geddes as “my singer,” which is a bit ironic considering how much of the song is sung by people not named Geddes.

The point is that with all these reprises and choruses, there’s not much time to tell the story, which is fine because it’s both simple and shocking. Julie calls up Joey to warn him that her Dad is really mad at him, and Joey heads straight to her house, and she ends up dead. Now, the classic teenage-love-death song tends to have death visit the guy, but here the girl not only dies, but she is shot by her own dad when she gets between his gun and Joey.

Let’s pause for a second and consider this. I mean, it appears Joey knocked Julie up, sure, but her Dad is shooting him from his own doorway – it’s right there on the cover in the pictures. What the hell? This doesn’t even qualify as “Stand Your Ground,” which, I will note, wasn’t even a thing in 1975. Dad doesn’t even have the energy to track down Joey, but apparently waited at home for Joey to show up. Oh wait, Julie called Joey and told him that her Dad was coming to get him. So, I guess he does have the energy to go get Joey, and maybe he went looking for him and then came back to the house. Of course, Joey goes to Julie’s house to see her, even though it would be smarter to tell her on the phone, “Hey, let’s meet somewhere secret – any place other than where I live or you live.” But he doesn’t, he goes to her house, and her Dad sneaks up behind him, as the lyrics explain, although in the pictures Dad’s coming out the front door, as I mentioned, so I’m not sure. It’s all just too confusing. I’m left wondering where his parents are in all of this, and, if maybe once Julie mentioned, “he’s got a gun,” he might have contacted the police. Was there an outstanding warrant for Joey? Is Julie as young as she sounds, and we’re talking statutory rape or worse? So many questions.

Following her shooting, but before she dies, Julie appears to think the best move for Joey, who is innocent in all of this (except for the getting-Julie-knocked-up part), is to run. Yeah, that won’t look suspicious at all. But, again, can we get their ages? Maybe in the liner notes?

I’m left wondering how it became a minor hit. Although the lyrics do present a short story, which might engage us, it is one of tragic young love, not the sort of thing we typically wanted to hear about on our transistor radio at the beach. Mix in the bits that don’t make a lot of sense, and one could argue that hearing this story multiple times would not typically lead to some deeper insight the way a Pink Floyd concept album might. The music itself is stereotypical, harking back to the early rock sound, the sound we associate with the teenage-love-death songs of the early 1960s. The changing voices – chorus, Julie, Joey – do provide more interest in that area than the typical pop song, but I’m not sure that’s enough to justify the song getting to number four on the hot 100.

Yep, Run Joey Run had a small run up the singles charts and peaked at #4 in the week of October 4, 1975. Number 5 that week (and the song that replaced Joey at #4 the next week) was the novelty hit Mr. Jaws. If you don’t know about Dickie Goodman’s novelty records like Mr. Jaws, they’re easy to describe. Our over-caffeinated announcer interviews someone fictional (like the shark and other characters from the movie Jaws) and that character answers in carefully chosen clips from popular songs of the day. Kind of like sampling before sampling. The shark might answer a question with “Why can’t we be friends?” ripped from the War song of the same name. It’s funny, see? (Full disclosure: I was given a 45 of Mr. Jaws as a gift for Christmas 1975 – so, yes, I actaully owned this record.)

It is not, however, really a song, so perhaps it is fitting that Joey was displaced by Mr. Jaws. If you were wondering what sat at #1 that week, it was Bowie’s Fame. The takeaway? The distance between #1 and #4 is much, much greater than “3.”

I promised to talk about the rest of the album, which was presumably quickly assembled after the single took off. There is some soft disco and some soft rock, but most is quickly forgettable. Some lowlights:

In Frankie, I’m so Sorry, out protagonist is not apologizing for running out on Frankie, but rather for teaching her to dance. Clearly, there’s some confusion about what an apology is for. Anyway, now she’s so good at doing the hustle, she won’t dance with him. Which, again, seems to misconstrue how teaching and learning work in the real world. Not to mention how a relationship should work.

The best parts of the song are the spoken-over-music bookends where the guy and his friend talk (and explain the premise in the process). You know you are in for a treat when the first words, spoken in an obvious New York accent, are, “Hey Joe, ain't that your old lady out there on the dance floor?” He soon follows with a wolf whistle. Classy.

Rounding out side one, is Wait For Me, which has just about the creepiest concept ever for a love song. “Johnny” tells us that she was only three when they first met. She grows up during the song. At each age, she tells him she loves him, singing “wait for me, I’ll grow up as fast as I can.” Like Joey, this is sung by an uncredited female (or females). The three-year old version is so unsettling, it puts into question the judgement of anyone at the recording session. Who said, “That’s it. That pre-permanent teeth sound is exactly what we were looking for”?

In case you were worried, the plot-twist at the end is that she ends up marrying someone else after asking him to wait for all those years. I’m not sure what the message is. It might be “marry ‘em as young as possible or else you’ll lose ‘em,” but I’m hoping not.

(Sidebar: Notice, so far we’ve had a Joey, Joe, and Johnny. Get this guy a baby-names book.)

The second side contains a bit of humor, one of the few bits on the record that reveal a human might have be involved in this project: Side 2 is not called “side 2,” but “The Other Side.” Now, when a famous comedy troupe did this a few years earlier, they at least had the smarts to call side 1 “This Side.” The fact that nothing else in the packaging or on the disc smacks of this kind of hip slyness ends up making this little joke just as baffling as most of the rest of the project.

Regardless, “the other side” skews a bit more country. The first song, Sneaking ‘Round Corners, sounds like non-threatening mid-70s country, with a slightly gospel chorus joining in for the refrain. The next number, What Will My Mary Say, includes another female voiced part, again sounding a bit too young.

Later on, When You’re Number One is told from a point of a superstar from the ghetto who has it so tough now that he’s “on top” because when you’re number one, “there’s nowhere else to go.” Consider Geddes’ trajectory after Run, Joey Run, not to mention the milquetoast music under the incipit lyrics in this song, and, well... let's just say the irony runs deep. And no one will ever mistake the singer of this song, or anyone associated with this song, as being from the ghetto. No one.

The final cut on the album, Let Me Hear It Out There, is in a genre that might be described as “big number with live crowd sounds.” For example, Ringo Starr’s I’m the Greatest is in this genre. I’ll be honest – this is easily the best cut on the album, and someone ought to consider creating a good cover version of it. Reminiscent of a Monkees tune like Listen to the Band (which also has crowd noises), the opening chords are a pleasantly surprising I to bIII progression (C-flat major to E-flat major), which is especially striking after nine songs with absolutely nothing, musically speaking, with any teeth. I imagine it's a bit like finding an oasis in the desert: the water tastes better simply due to the context.

It’s too bad that the song is ultimately ruined by an over-literal interpretation of its theatrical lyrics, par for the course on this album, anchored – need I remind you? – by a teenage-love-death story song.

Let Me Hear It Out There carries over the theme of fame and its burdens from When You’re Number One. The lyrics increasingly talk of isolation as the song goes on, even to the point of our protagonist abandoning his wife and child (!), which might not be so shocking to us after hearing about accidental filicide, implied pedophilia, and dance-instructor-abandonment. Unfortunately, producer Paul Vance decides to go literal again. So as the words get more depressing, the crowd goes away, instruments drop out, and the volume and energy disappear, until the voice of Vance’s singer, David Geddes, is all that is left. The album ends with literally a whisper.

Two years after Run, Joey Run, Meat Loaf and Jim Steinman, with producer Todd Rundgren, would get the over-the-top story-song album equation right with Bat Out Of Hell. Steinman might have ended up resenting his singer, but better that than creating the mess that is Run, Joey Run, which seems to have gotten stuck firmly in hell.